Some notes about Drewsteignton during the Eighteenth Century

By Paul Greener

The Laity

Four local families stand out from the rest during the century and could be seen as minor gentry or prosperous yeomen depending on the eye of the beholder. Until they bought their farms at auction in 1791 the Ponsfords, between them, leased over 550 acres from the Carews and the Pitts leased a profitable limestone quarry. The Braggs leased nearly 300 acres and the Battishills owned as much. During the century these families all provided churchwardens as did 26 others who would have been considered to be reputable if not prosperous. When the Oath of Allegiance was demanded in 1723 the prominent families turned out in force with no less than five William Ponsfords signing as well as a John and a Thomas. Anyone who thought they had something to lose by not swearing would have presented themselves and there were 87 properly recorded names of parishioners who either attended at Crockernwell or at Exeter Castle. The Appendix gives a complete list with some detail where possible. Fourteen of those names do not appear in any available records so they may have been settlers in recent years. Of the 23 women who took the oath, as only three were literate, the men could not have learned how to write from their mothers. The village school had been open since at least 1665, when it was first mentioned in the churchwardens' accounts,8 and it would appear that half the oath takers, that is 30 out of 63 males, had been scholars there. The local families were possibly not grand enough to engage private tutors.

On 18 December four ladies and a Joseph Cheeseworth, all of them illiterate, were the only local oath takers at Exeter Castle. It may not be too fanciful to suggest that he escorted them on what was also a shopping expedition.

Although the percentage of literate male oath takers was 48% it would be interesting to discover the overall literacy of the parish based on the ability to sign one's name if nothing else. Back in 1641 only eight men were able to sign the Protestation out of a male population of 192 - a mere 4%.9 There are two ways in which an estimate of the 1723 parish population may be made:

- An average of Dr. Rennell's family numbers in his 1744 return is 110 which multiplied by a notional 4 ½ gives a figure of 495.

- In 1811 the churchwardens enclosed 'An Account of the Poppelation of Drewsteignton ' with their ordinary accounts.10 They recorded 209 families living in 205 houses with a total population of 998. Working back from this figure and subtracting the numbers of baptisms less the number of burials between 1723 and 1811, which comes to 527, we arrive at a figure of 471. There had been 29 more baptisms than burials between 1723 and 1744 which taken away from Dr. Rennell's adjusted figure gives 466.

Without excessive speculation, and assuming that the 1723 population numbered about 470, at least 6.4% for all adults and possibly 27% of males could write their signature and possibly more of them could read a little.

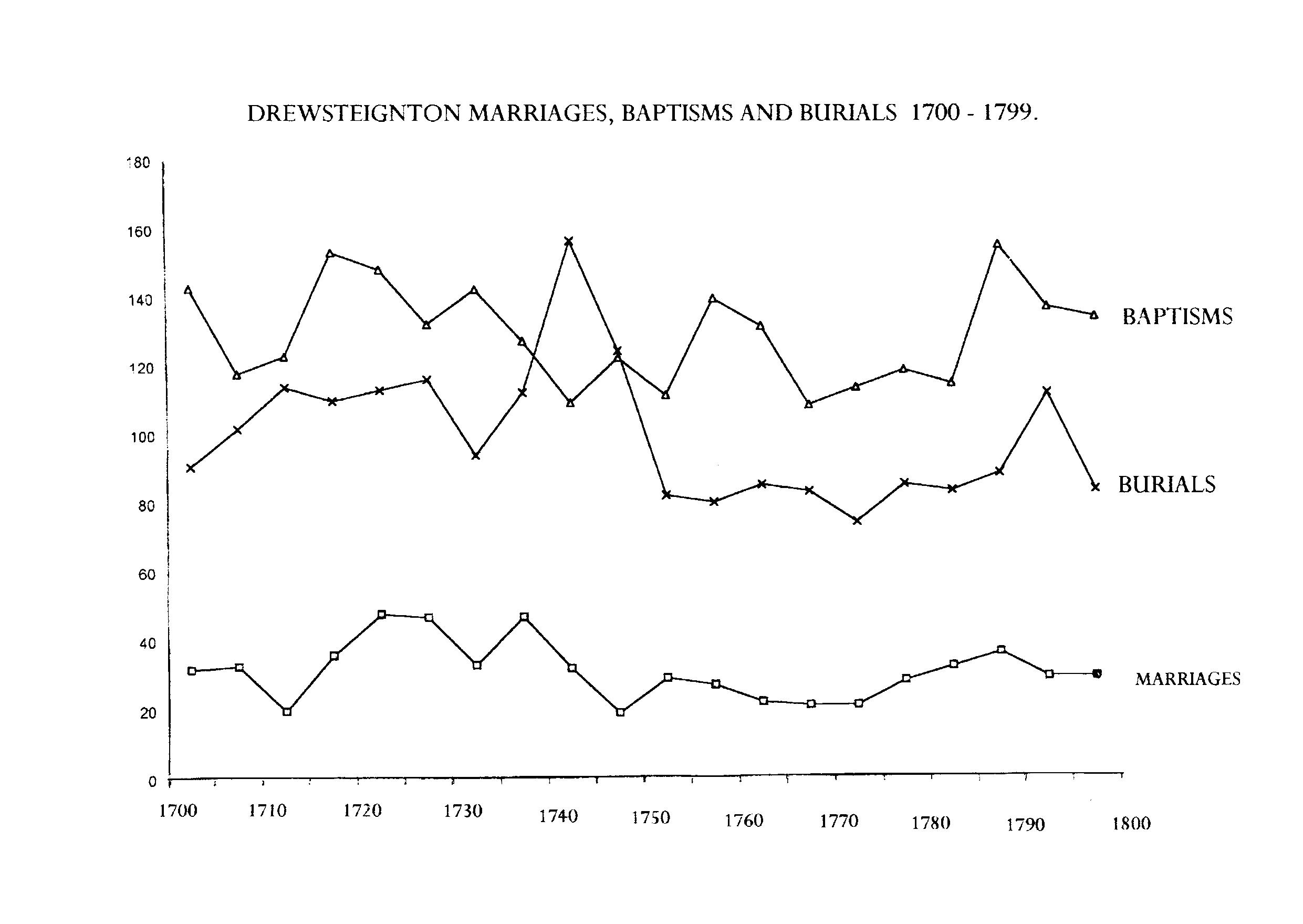

The chart below is compiled from the parish registers of marriages, baptisms and burials from 1700 to 1799.11

There is much to be learned from the chart although it only shows aggregate figures in five year periods. The population increased steadily until mid century and then burials, on the whole, declined allowing numbers to increase dramatically. What is not shown are the 56 burials in the year 1711-12, more than twice the average at that time. A young girl from Morchard Bishop was buried on 8 August and soon afterwards it appears that a deadly epidemic spread through the parish for about four months killing at least 22 children under the age of seven and a number of adults including the Rector who died in September. This was possibly a type of influenza since the young appear to have been particularly susceptible. A prominent peak in the graph of burials in 1741-42 is probably due to an extremely cold winter when there was an almost continuous frost for eight weeks which contributed to the 45 burials that year.12 An index of marriages not only indicates the availability of young courting couples but also their expectations and this is apparent from the time lag on the chart.

Continue to next section Return to previous

- DHC, 2165/A/PW2, Churchwarden's accounts 1661-1698. [back]

- T.L. Stoate, The Devon Protestation Returns, 1641 (1973). [back]

- DHC, 2165/A/PW2, Churchwarden's accounts 1792-1886. [back]

- DHC, Drewsteignton Church registers on fiche. [back]

- See 'Observations on the Air and Epidemic Diseases' Dr. John Huxham. Copy in Met. Office, Exeter. Quoted by W.G.Hoskins, Old Devon (Newton Abbot, 1966). See also Neville C. Oswald, 'Epidemics in Devon, 1538-1837', Trans. Dev. Assoc. , 109 (1977), 73-116. [back]